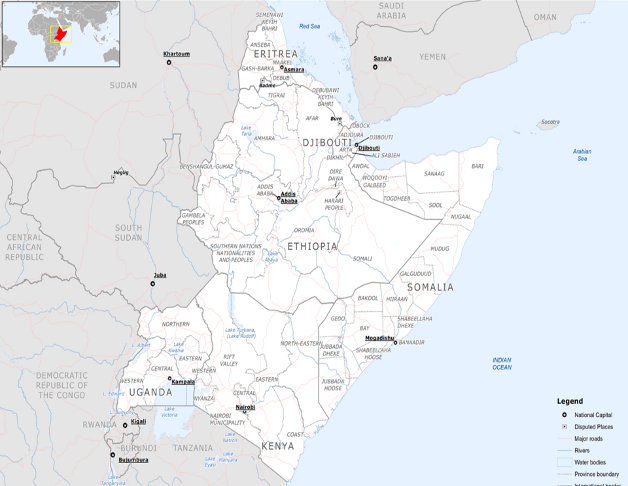

The growing presence of Gulf states in East Africa has shaped a notable commercial landscape in the region. Motivated by national goals and regional rivalries, countries such as the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Saudi Arabia, and Qatar have utilised infrastructure investments, particularly in ports, to expand their influence along the Red Sea corridor.

Africa’s Red Sea coastline sits at the cross-section of three continents and significant maritime trade routes. Previous Western engagement with this region of East Africa has traditionally centred on aid and institutional reform. In recent years, the Gulf states have introduced a different approach through commercial investment and ambitions to exert their influence. Influence, nations such as the UAE, Saudi Arabia and more recently, Qatar have heavily invested in infrastructure. Often, with more direct financing and fewer international regulations compared to previous Western states.

The UAE has emerged as a key player and the largest investor in Africa. They have achieved this by endorsing state-backed entities, such as DP World and AD Ports, to secure operational control in ports. Across Djibouti, including Berbera, Bossaso, Kismayo, and Port Sudan.

Saudi Arabia has invested $13 billion of the $15.6 billion allocated to Djibouti, supporting energy infrastructure and logistics parks near the Bab al-Mandab Strait.

Qatar, like the UAE and Saudi Arabia, has utilised aid, investments, and diplomacy to exert influence in East African states, particularly Somalia and Sudan.

Together, these Gulf nations have established a powerful. Fiscal presence in one of the world's most geopolitically vulnerable regions.Their approach marks a clear departure from Western-led aid models, replacing them with rapid state-directed investment aimed at long-term strategic control.

A central policy of Port development projects has become the central policy of. Gulf states and their strategic engagement in East Africa. This is notdissimilar to China’s recent approach in the Caribbean. Two factors drive this trend of port investment:

Gulf states are investing in Red Sea ports, such as Port Sudan and Berbera, to reduce their reliance on the Strait of Hormuz. By diversifying oil export corridors, the UAE and other countries aim to limit their vulnerability and expand their influence in a contested maritime zone.

Gulf port deals are increasingly incorporating security components, granting states like the UAE a naval presence on the African coast. In Berbera, the UAE funded a major port upgrade alongside a nearby military base. These moves reflect a broader strategy to anchor power along the Red Sea and extend its reach toward the Mediterranean.

East African governments widely welcome Gulf capital, but it often bypasses the usual development protocols. Unlike Western institutions, which attach governance and transparency conditions to aid, Gulf investments tend to be state-directed and have less regard for regulations.

This dynamic has raised concerns among local governments across the region. In Djibouti, disputes have arisen over the terms of Emirati-backed port projects. The government unilaterally scrapped a 50-year DP World port concession in 2018, claiming the deal ‘compromised national sovereignty’ by giving excessive control to the UAE. The move caused international arbitration, with courts repeatedly siding with the Emirati firm. Djibouti’s decision to hand over operations to a Chinese state-linked company further fuelled concerns over external control.

In Sudan, the UAE’s involvement with rival political factions has complicated peace efforts. A $6 billion port project was cancelled amid the country’s civil war after Abu Dhabi was accused of backing one side with arms. This only further highlights Gulf state interference and disregard for regional stability.

The strategic consequences of Gulf expansion in East Africa are considerable. Gulf capital has spurred much-needed infrastructure development, but the accompanying political consequences are reshaping regional dynamics. This is often to the detriment of traditional Western influence and access. Key risks include:

• Restricted Access: Gulf companies’ control of critical ports, from the Suez to Bab al-Mandab, potentially could squeeze Western competitors out of the region. For example, when Sudan made port deals available, Western firms found themselves losing out to Gulf (and Chinese) bidders amid a lack of transparency in negotiations.

• Dependencies: Gulf financing can create debt and dependency that limit East African governments’ ability to act in the future. Reliance on a single wealthy investor may constrain the country’s ability to make sovereign decisions, especially if port revenues or loans are effectively tied to Gulf security interests.

• Heightened Instability: Gulf rivalries are being imported into an already unstable region. Gulf states are injecting resources and exporting their rivalries into the Horn of Africa in ways that will almost certainly cause more regional risk.

Gulf engagement in East Africa is not only about investment; it’s about influence, competition, and long-term alignment. Each major Gulf player has a different grand strategy for their investment. The UAE pairs commercial ports with military access, Saudi Arabia is prioritising Red Sea security, and Qatar are trying to leverage influence through financial diplomacy. For East African nations, Gulf investment presents an opportunity but also brings growing instability. While it offers much-needed revenue, it must be balanced against the risk of trading sovereignty for short-term financial gain. For Western actors, matching Gulf capital and geographic proximity is not feasible; the challenge is to offer competitive alternatives that maintain some regional stability.