Libya occupies a pivotal position at the crossroads of Africa, the Maghreb, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean. It holds Africa’s largest proven oil reserves, approximately 48 billion barrels. Despite more than a decade of volatility, the Libyan oil industry and institutions such as the National Oil Corporation (NOC) and the Central Bank of Libya (CBL) have endured. Oil still provides over 90% of Libya's state revenue, paying for wages, subsidies, and imports that sustain the country’s society.

However, oil wealth provides both economic rewards and simultaneously creates risk. It keeps the economy afloat but is contested by rival governments and militias. The outcome of this is a nation that is not collapsed but fractured, where rival groups profit from instability.

For individuals or organisations, Libya presents an uncertain and often hostile environment. Oilfields and export terminals are contested by militias and foreign mercenaries, with blockades and clashes regularly halting operations. Security is frequently controlled by local groups whose loyalties shift, creating exposure to extortion, sudden contract breakdowns and reputational risks through association with smuggling networks. Among all African countries, Libya was ranked the 9th most fragile in 2024.

The oil sector remains the backbone of Libya’s economy. The NOC’s bureaucratic neutrality has allowed production to continue during the civil war. The CBL uses oil revenues to fund nearly 2 million public salaries and maintain broad subsidies.

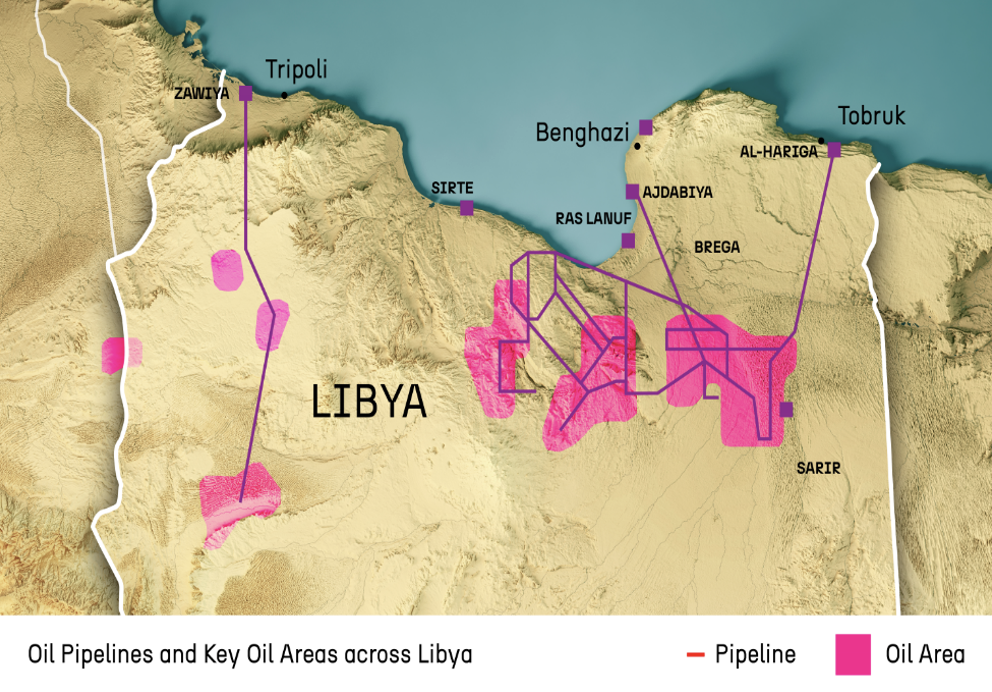

However, oil in Libya is not only an economic lifeline but also a commodity that fuels political rivalries and deepens instability. In Libya, the oil fields and export terminals are contested between the Government of National Unity (GNU) in Tripoli and Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA), with both groups continually competing for control.

The Sirte Basin, also known as the ‘oil crescent’, has been repeatedly blockaded, slashing output by hundreds of thousands of barrels per day. Losses since 2011 are estimated at over $160 billion.

Libya’s subsidies make its fuel among the cheapest in the world. A litre bought cheaply domestically can sell for 20-30 times more in Tunisia, Malta, or Italy. Militias and criminal syndicates use this to their advantage and use the subsidised fuel from depots and refineries, moving it by land and sea.

Profits from subsidised fuel sales abroad drain the national treasury while reinforcing the power of militias that control Libya’s oil infrastructure. A prominent example of this came in September 2017, when the NOC accused a militia of diverting fuel. The group retaliated by cutting power to western Libya, forcing the NOC to back down. Therefore, subsidies intended to help citizens can often end up funding armed groups.

Other illicit trades overlap with fuel smuggling, creating alternative networks of power. The same groups often manage multiple trades. Smuggling revenues also diversify militia incomes, ensuring they have no incentive to relinquish local control. More examples include:

• Human Smuggling: Libya remains the main departure point for migrants crossing to Europe. Coastal towns like Zawiya and Sabratha have militias earning millions from extortion.

• Arms Trafficking: Weapons from Gaddafi’s stockpiles have spread across the Sahel, continuing conflicts in countries like Mali.

• Drug Trafficking: Hashish and synthetic drugs transit through Libya’s ports and coasts toward Europe.

Libya does not function as a unitary state. Rival governments in Tripoli and Benghazi claim legitimacy, while real power lies with militias that act as both protectors and profiteers.

Formal institutions persist, but armed groups gatekeep them. Militias in Tripoli and the east extract rents from ministries, checkpoints, and oil terminals. Officials often collude with smugglers and attempts to bring such groups to a stop have been met with violence or political pushback.

In this system, governance is regularly transactional, negotiated between central institutions and individuals of importance within militias. Illicit activity and state functions are intertwined, making underground economies a central feature of how Libya is governed.

Libya’s vast deserts and porous borders with six countries are nearly impossible to secure. Smuggling routes across the Sahara link sub-Saharan Africa to Mediterranean ports. Tribes like the Tebu and Tuareg manage stretches of frontier, sometimes in collusion with smugglers.

The geography of oil compounds the problem. The most affluent oil fields are located in contested central regions, while export terminals along the Gulf of Sirte sit on fault lines between east and west. Meanwhile, the long Mediterranean coastline provides routes for both crude exports and contraband. Geography itself sustains fragmentation by making local control profitable.

External actors have reinforced Libya’s fragmentation:

• Europe: Italy struck deals with coastal militias to stem migration, legitimising smuggling groups like Sabratha’s Dabbashi clan. Furthermore, the EU’s support to Libya’s coastguard has arguably empowered militias complicit in trafficking.

• Russia: Wagner Group mercenaries guard oilfields and terminals under Haftar, giving Moscow leverage over exports. Wagner-linked networks are also accused of facilitating fuel smuggling into Sudan’s conflict. As seen in our previous Sudan report.

• Turkey: By rescuing Tripoli in 2019-20, Ankara secured maritime rights and future reconstruction contracts. However, it supports entrenched Western militias.

• Egypt and UAE: Both support Haftar, viewing him as a barrier to extreme Islamist groups. Their support has bolstered the LNA, which in turn relies on revenues from smuggling and oil.

Each foreign influence continually adds to Libya’s smuggling economy rather than dismantling it.

Oil revenues are distributed nationwide, even indirectly funding Haftar’s forces. Instead of fostering unity, this enables rival factions to finance patronage networks.

Transparency initiatives, such as a UN brokered audit of the Central Bank, have made little progress. NOC attempts to shut ‘ghost’ petrol stations were blocked by political leaders, prompting accusations of state capture.

This only further fuels corruption, erodes the rule of law, and undermines public trust.

• Energy markets: Output swings from 0.2 million to 1.2 million barrels per day and can impact oil prices and complicate OPEC policy.

• Migration: Smuggling networks have a direct influence on European politics, with migrant flows shaping elections in Italy and elsewhere.

• Regional security: Libyan arms have destabilised the Sahel, while fuel smuggling disrupts Tunisia’s economy.

• Organised crime: Hybrid networks link militias to global illicit markets, complicating counterterrorism.

Libya is best described as a fragmented nation. Oil sustains the economy but also fuels rivalries and criminal activity. Smuggling has become integral to governance, entrenching militia power and fragmenting sovereignty. Breaking this cycle would require unified institutions, transparency over revenues, and reform of subsidies. This would focus on measures that directly target entrenched interests. Until then, Libya will remain caught between wealth and instability, meaning it is wealthy in theory but fragile in practice.