The Lobito Corridor is one of Africa’s most ambitious trade and infrastructure projects. It has been designed to unlock the continent’s economic potential while navigating substantial investment risks and it is centred on a revitalised 1,300km railway. According to the World Bank, this corridor aims to be the crucial linkage for critical minerals like copper and cobalt.

Western governments have championed the project under the G7’s Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment. Some even see the project as an alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Although some Chinese firms, who helped rebuild the railway and dominate regional mining, are also set to benefit, underscoring a complex mix of cooperation and competition.

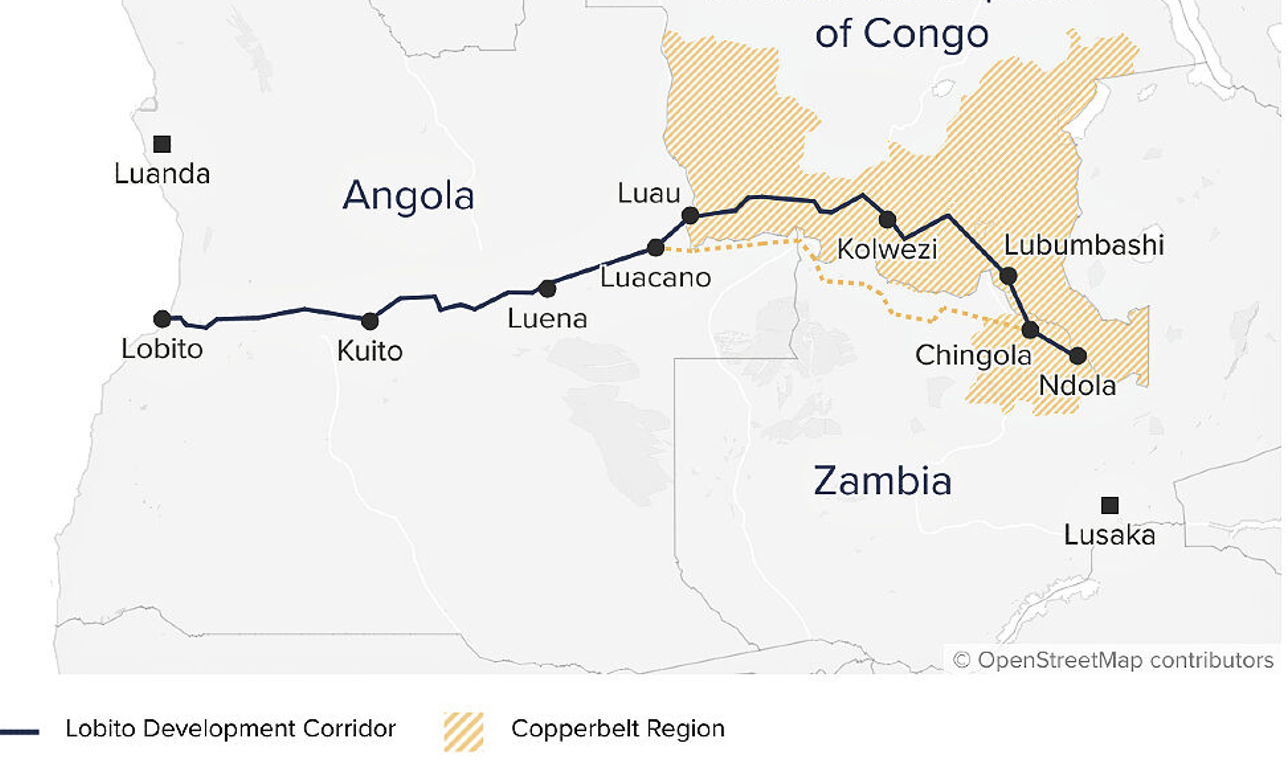

The Lobito Corridor runs from the coastal city of Lobito in Angola, across the country’s highlands to the DRC border and then onward to Kolwezi in the southeast of DRC’s copperbelt. It has planned for a branch line to extend to neighbouring Zambia.

In total, the rail link spans roughly 1,344 km from Lobito to the DRC border, plus another 400km into the DRC mining zones. First developed as the Benguela Railway in 1931, the route was once central and Africa’s main export outlet to the Atlantic. But decades of Angola’s civil war destroyed large sections, forcing Congolese and Zambian exporters to use longer eastward routes via Dar es Salaam or southward.

A reconstruction effort began in 2004 under a $2 billion oil-backed infrastructure deal with China. This meant the Angolan section was fully rehabilitated by 2014. The corridor now is regaining strategic significance as both a shorter and cheaper alternative to eastbound routes such as the Tazara railway to Tanzania or Mozambique’s Beira port. It links the DRC (containing 70% of the world’s cobalt reserves) and Zambia (Africa’s second-largest copper producer) directly to an Atlantic port integrating these resources into global supply chains more efficiently.

The corridor has attracted substantial financial commitments from both public and private actors. The United States, European Union, and African Development Bank have pledged more than $10 billion for infrastructure and support programs.

In 2024, Washington announced an additional $560 million in funding, bringing US commitments above $4 billion. With EU and AfDB contributions, combined Western and multilateral investment had risen to over $6 billion by the end of 2024. These funds target infrastructure, rail and port upgrades and bureaucratic measures like customs reforms and workforce training. The private sector is also key. A consortium led by Trafigura and Belgian operator Vecturis won a 30 year concession in 2022 to run the Angolan rail segment. It has committed more than $550 million in new locomotives, wagons, and training programs to boost freight capacity.

Despite such investment’s, challenges remain. Angola has pursued reforms since 2017 to attract investors but debt and corruption are prominent. Zambia’s business climate has improved, supported by IMF-led debt restructuring and anti-corruption reforms. The DRC, however, remains highly volatile, ranking near the bottom of global governance and corruption. For investors, this mix creates a dilemma, the minerals underpinning the global green transition remain in the corridor where political and financial risks remain acute.

Security risks are significant. In the DRC’s copperbelt provinces, entrenched trucking cartels and informal operators benefit from the status quo. Reports describe truck drivers paying bribes at approximately 15 illegal checkpoints between Kolwezi and the Zambian border. Introducing a modern rail system poses a threat to these networks, raising the risks of disruption and protests. Angola’s corridor zones also remain contaminated by landmines from the civil war, which pose operational hazards.

Beyond physical risks, the corridor has become a stage for global competition. Western partners view Lobito as a means of securing diversified access to cobalt and copper, thereby reducing their reliance on China’s infrastructure and processing capacity. Plans even envision eventually linking Lobito to Tanzania’s Dar es Salaam port, creating a trans-African rail corridor from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean. China’s role is more complex. Having financed Angola’s rail rebuild and invested billions in Congolese mining, Chinese companies, like Zijin, are already booking shipments on the Lobito line. This is geopolitically significant because it shows that while the West frames Lobito as an alternative to the Belt and Road, African states are determined to keep both Chinese and Western partners interested to maximise investment and bargaining power.

Governance is a central risk. Angola and the DRC remain among the most corruption-challenged states globally, with Transparency International scores of 32/100 and 20/100, respectively, while Zambia ranks better at 39/100. These weaknesses affect everything from contract allocation to customs enforcement.

Furthermore, there is a lack of streamlined customs and the corridor risks becoming as inefficient as existing truck routes. Regional frameworks under the Southern African Development Community and the African Continental Free Trade Area are promoting digitised systems and standardised procedures. The involvement of multilateral financiers like the AfDB and European Commission creates pressure for transparency. The private concessionaires also bring compliance standards that may raise accountability. But the risk remains that networks in Angola and the DRC could capture corridor revenues unless regional oversight is sustained.

The Lobito Corridor encapsulates much of Africa’s political and investment climate of potential and risk. It offers a route to integrate Africa’s mineral wealth directly into global trade, cut export costs, and foster industrialisation. However, to do so means navigating past obstacles like entrenched corruption, security risks, and political fragility. For local communities, the corridor could bring jobs and infrastructure if managed correctly. For investors, it offers high rewards tied to the global green transition but only alongside substantial risk. The Lobito Corridor may yet become a model for how infrastructure can drive development across Africa.